In December of 1769, Richard Henry Lee was Seeking Facts over Emotion: The Road to Revolution

Introduction: shades of gray in primary sources.

Fact vs. fiction. Objective vs. subjective. Primary vs. not.

Primary sources are something I strive to focus on as I continue to learn and understand our shared American history.

Let's start with this: what is a primary source? Examples below:

- letters, journals, and diaries

- daybooks and account books

- inventories and receipts

- official government documents from licenses and certificates to court orders and transcripts

- newspapers, pamphlets, and publications of a period

- art and objects: from paintings to pottery

Are you already categorizing the above-mentioned in your head? Let me complicate it further.

- oral history

- holiday traditions

- family traditions

But what can be distinguished as fact? As objective over subjective (even based on emotion).

As black and white, lacking the gray.

RELATED: Click here to read my introductory post about primary sources in a new tab.

Disclaimer: As a blogger, I use affiliate links sometimes! I may receive commission from purchases I share; it does not change your price but sometimes you might get a discount.

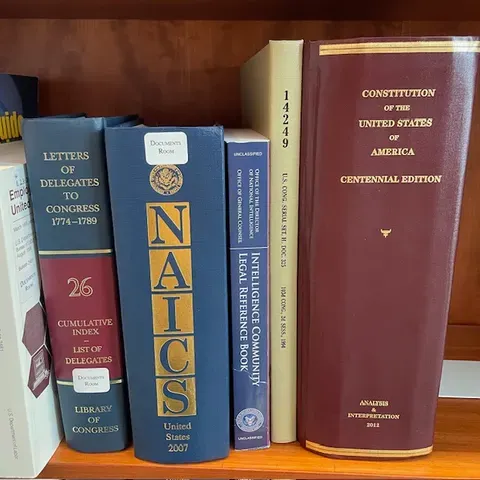

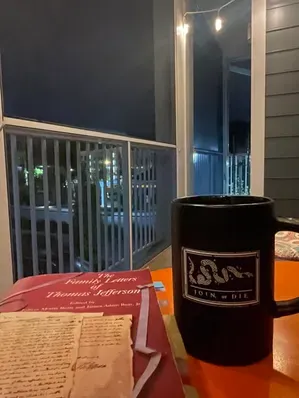

Bookshelf at the Library of Virginia (open to the public)

Is something factual just because it's primary?

The fast answer is NO.

The more in-depth answer: yes, with that bit of gray. Keeping in mind a few things about letters, journals, and diaries. Also art, newspaper entries, and more.

So much of these primary sources are up to interpretation. Which is why I struggle with secondary sources- such as biographers. They (hopefully) are basing writing on primary sources, but then- you're reading their interpretation of it.

A reason why interpretation by others needs to be a matter of trust. And citation- so you can see the primary source for yourself; maybe re-interpret.

Differentiating between facts over what may be subjective interpretation, even in the historical source, is important in learning history. Or even what's contemporary.

A fact: the price paid for a service or product.

Example: January 5 and February 9, 1807, Thomas Jefferson paid 5 D (dollars) to Connor the barber. In fact, he paid Connor most months, but may have seen a different barber in August. It cost 3 instead of 5, and the barber is not named.

Daily life, the cost of whatever service he was getting (wig maintenance?), habits and accounting... so much can be gleaned from Jefferson's account books.

But what we know for certain is that, according to Jefferson's own accounting, he paid the amount he paid, and to whom he paid it.

Click here to view the source on Founders' Archives.

My copy: The Family Letters of Thomas Jefferson

A fact: criminal charges against someone and the court's verdict.

Example: In 1802, 15 men including a man named Benjamin Cummings, were found guilty of failing to vote in the "last election" in Loudon County Virginia. In the same year, over 30 men and 1 woman named Grace Vers were charged with "swearing" there.

And not all were found guilty.

Click here to see the listing in Loudon County's court records which include both Cummings' and Vers' cases.

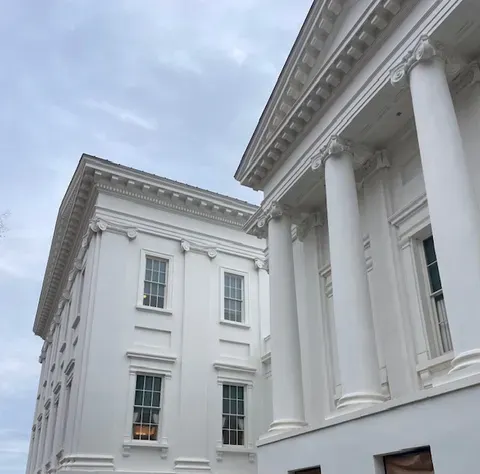

A fact: the date of a legislative session.

Example: Virginia's General Assembly began their October 1792 session at the Capitol in Richmond on Monday October 1st.

Citation: October Session, 1792, published by the Virginia State Library, Richmond, 1949, page 1.

But let's be 100% honest: these are all transcribed.

There's a level of trust necessary unless you hit the courthouse's archives room or the special collections of a museum, library, or historical society. Finding a trusted source is something I always strive to do.

One such trusted source is Dr. Gordon Blaine Steffey, Stratford Hall's Vice President of Research and Collections and their Director of the Jessie Ball duPont Memorial Library.

Therefore, I trust the transcribed letters on Stratford Hall's website.

Virginia State Capitol, Richmond

So who was Richard Henry Lee?

Where to start?

My fascination with Lee is as layered as an onion. He and his family are mentioned multiple times on this blog and will continue to be.

Lee was raised at Stratford Hall and had relationships with all the names familiar to history-lovers: George Washington, Patrick Henry, and more.

Heavily involved in politics during the Revolutionary era, he had multiple siblings also heavily involved. In Philadelphia representing Virginia during the summer of 1776, he was the one who introduced the resolution to declare independence.

The vote was taken on July 2nd, in advance of the declaration to the world being adopted on July 4, 1776.

In short, Lee is someone whose name should be a household one if anyone asks my thoughts.

RELATED: Click here to read my interview of Frank C. Megargee, long-time interpreter and historian of Richard Henry Lee.

Walking the grounds at Stratford Hall, RH Lee's family home

Why 1769 was important on the "road to revolution."

If you've been following this blog, reading about the American Revolutionary War, been watching Ken Burns' 'The American Revolution,' visited historical sites including Colonial Williamsburg, Stratford Hall, or the American Revolution Revolution Museum at Yorktown, you likely know that the "revolution" didn't start in 1776.

Many posit that 1) July 4, 1776 wasn't "the beginning" so to speak and 2) the American Revolution is ongoing.

The 1760s were pivotal in what's commonly referenced as the 'road to revolution.' From the Stamp Act to the Declaratory Acts, Parliament seemed to be on a mission to alienate residents of British Colonies. (read more about the Stamp Act and Patrick Henry's Resolves here)

Remember the actual line often quoted is "taxation without representation," not just "taxation." Parliament had spent years building a negative relationship with British subjects living on this side of the Atlantic.

In researching Richard Henry Lee's role in our nation's founding, I ran across a letter that draws a line under the value of "fact" and "objectivity" in a primary source over the subjectiveness and potential interpretation in a letter.

During the month of December, 1769, Lee wrote his brother William who was in London. At the time, William was serving as a "commercial agent for Lee family enterprises abroad." (quoted directly from Stratford Hall's website.)

Richard Henry Lee was seeking the truth about Parliament's activity. As tensions grew, his goal was to report to the House of Burgesses in Williamsburg what Parliament was ACTUALLY doing in terms of American affairs.

Reading this bit of history, the words of a Revolutionary-era Lee I'm so invested in understanding and intrigued by, I had to pause and smile.

A spark was lit as I realized it's not just us in the 21st century who aim to base interpretation on facts, but those who lived our history want the same.

RELATED: Click each location previously mentioned to get tickets to visit:

The American Revolution Museum at Yorktown

Fresh Views of the American Revolution special exhibit, American Revolution Museum at Yorktown

Richard Henry Lee's words that inspired this blog post.

[Author's Note: one long paragraph is broken into three for easier reading.]

Richard Henry Lee to William Lee, December 1769

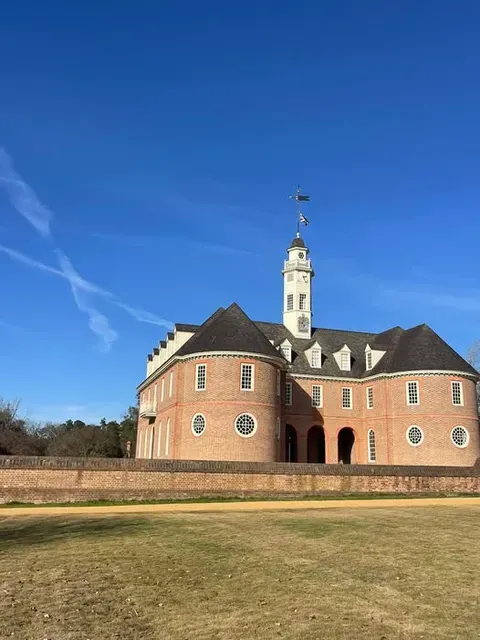

Williamsburg Decr. 17.[ – 20] 1769

Dear Brother,

At this place we have been confined since the 7th. of last month attending on the assembly, and here I have received your favors by Capt. Johnstoun and Mr. Adams. The business of the Country, not having been for three years considered, has occasioned this to be a meeting of so much business and great perplexity, that an adjournment to the middle of May will certainly take place.

We hope by that time to know the determination of Parliament on our affairs and would therefore wish to have the most early authentic intelligence on this subject.

And as scruples have arisen about the authenticity of

Click here to read the letter in full, with notes and citations, in the Lee Family Digital Archive, on Stratford Hall's website.

Reconstructed Capitol, Williamsburg, where RH Lee served in 1769

My conclusion on primary sources.

I'll still read all of them. Yes, letters, diaries, and even newspaper accounts- though they may seem subjective. In my opinion, they're vital to understanding the person who wrote it, the culture of a region, the events and the daily life of an era.

Theory over speculation- that's how I view it. Digging deep enough (or finding a trusted source who does) to put all the primary and secondary sources together to formulate an interpretation that's legit.

My recommendation: read any and all primary sources on any and all people, events, or topics you're interested in! And if you want recommendations, use the search bar at the top of the page and find links to dig deeper on them.

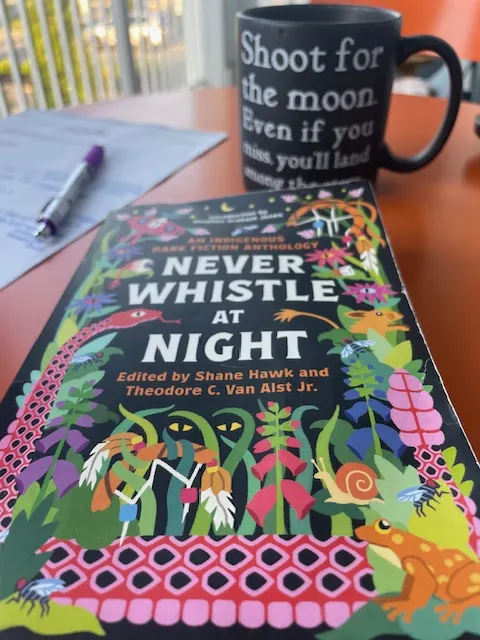

And if you want to bring primary-sourced education into your home:

Click here to shop my recommended resource: History Unboxed.

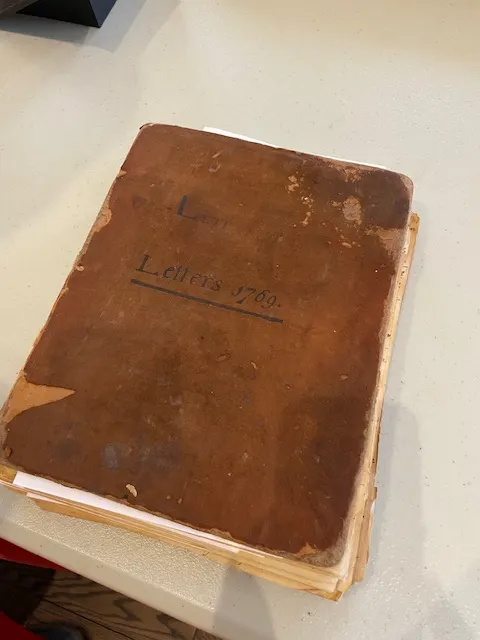

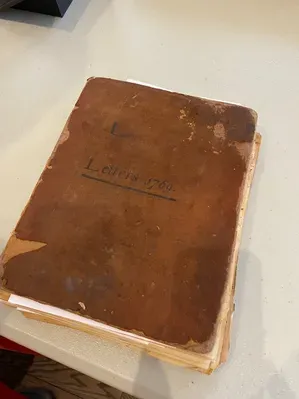

My closing "call to action" for myself: see if this letter is housed at Stratford Hall in their special collections- possibly in William Lee's letter-book (dated 1769!) from his time in London? I may have to reach out to my friend Gordon, who showed me the book...

Cheers!

William Lee's letter-book, Stratford Hall

Are you enjoying my free history blog? Tip me using my online tip jar to help keep me blogging!

There is a huge practical disclaimer to the content on this blog, which is my way of sharing my excitement and basically journaling online.

1) I am not a historian nor an expert. I will let you know I’m relaying the information as I understand and interpret it. The employees of Colonial Williamsburg base their presentations, work, and responses on historical documents and mainly primary sources.

2) I will update for accuracy as history is constant learning. If you have a question about accuracy, please ask me! I will get the answer from the best source I can find.

3) Photo credit to me, Daphne Reznik, for all photos in this post, unless otherwise credited! All photos are personal photos taken in public access locations or with specific permission.